Variations on that question make up a significant amount of the feedback I get here at music4dance. The first answer to these questions is that music4dance is crowd-sourced. So someone at some point said that they could dance that style to that song. They may or may not be right, but I think it’s worth stopping to think for a moment – is there a way they could they be right?

That’ s because of the second answer – which is that the dance world is diverse, so what people mean by naming a dance style can mean different things to different dancers. Now, I could lock down the site and say that only songs that meet a very specific criteria of being strict tempo for American Style East Cost Swing can be marked as Swing. There are advantages to being that strict – the biggest one is that it would make auto-generating playlists or rounds much more accurate. But the disadvantage is that it narrows the world of dance. Especially in these times I feel that it’s important to foster diversity even in the small ways, like what kind of music I would dance a swing to.

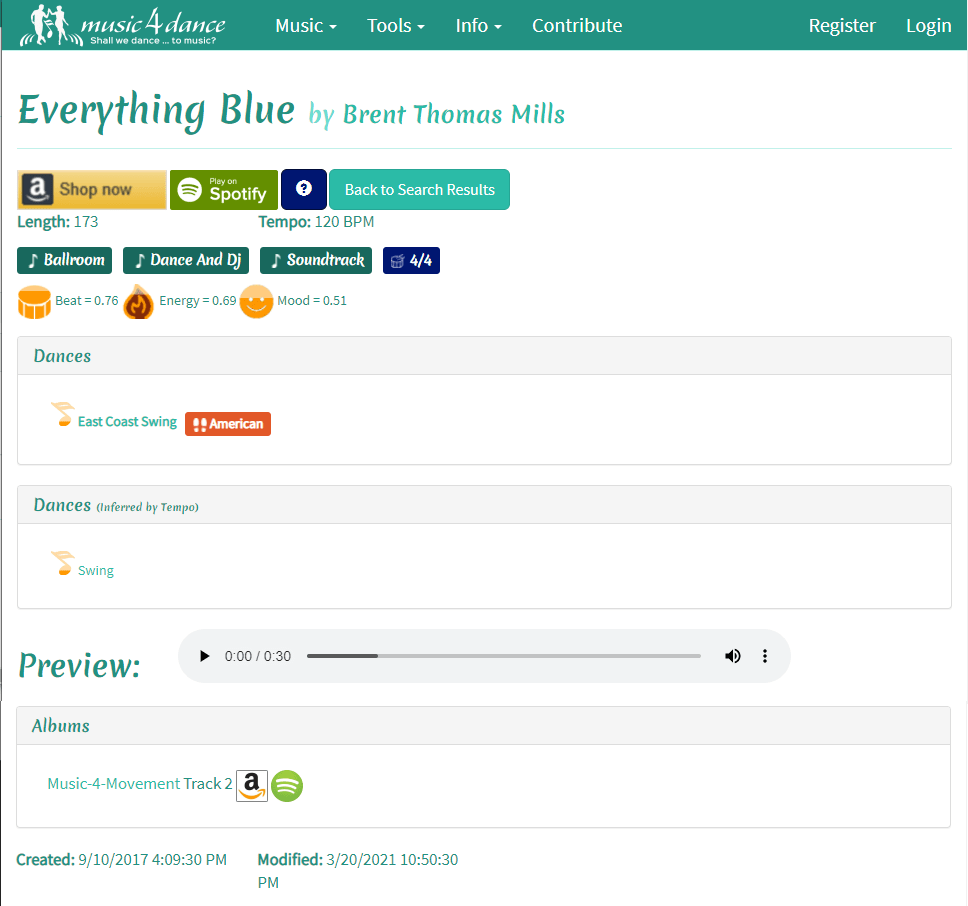

In any case, I bring this up now is in part because of a discussion I had with Brent T. Mills who found a song that he had produced listed on the site as a Swing rather than as a Foxtrot. He clearly intended this song to be a Foxtrot. And aside from the (very important) fact that he has every right as the producer of that song to assert what he intended it to be danced to, he and I both come from a ballroom background and so share the same definitions of dance styles, at least at some level. Mr. Mills also wanted to make it clear that his main interest in contacting me was to help avoid confusion for dancers that aren’t experienced enough to know that many songs have a lot of crossover rather than anything negative. I very much appreciate the sentiment – and he speaks from experience – check out what he’s up to at www.MusicMills.net.

The thing that I realized as part of this discussion is that it wasn’t obvious from the page that he landed on that the dance information was crowd-sourced. I hadn’t thought about that in exactly those term before, but as I’ve been reworking the site I’ve been trying to do a better job of re-using more common user interface elements than I did the first time around. In the particular case of the voting mechanism for dances I think this I’m making some progress in making things like the crowd-sourced aspect of the site more clear.

In the original version (which is the current version running on the site as of mid-march 2021) I have a musical note next to a dance style that is filled up (like a thermometer) based on how many votes it’s gotten. The only way to tell that this is a voting mechanism is to hover over the icon and read the text that says that this song has one vote. In my defense this is a little clearer when you’re on a page that lists a bunch of songs with their respective votes, but it’s still not great.

In the new version (which I hope to release shortly), I use what I believe is a pretty standard mechanism to indicate voting. At least this is how the Stack Exchange family of sites that I spend an inordinate amount of time handles voting. It’s the number of votes vertically framed by up and down arrows. Clicking on the arrows will allow you to vote (or ask you to sign in to vote).

What do you think, is the new version easier to understand? Or should I go back to the drawing board again? As always, I welcome feedback.

Quick Tip:

If you would like to vote on what dance you would dance to a song, create an account and start voting.